Shocking New Data Reveals: Are We Underestimating Climate Change by 50%? Find Out Now!

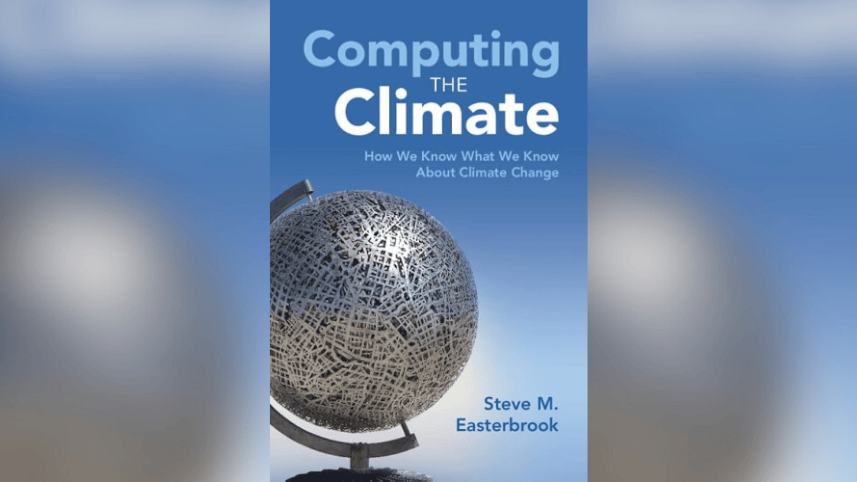

In the ever-evolving discourse surrounding climate change, a new book titled Computing the Climate by Steve Easterbrook stands out not just for its subject matter but for the author’s unique background. Holding a Ph.D. in computing, Easterbrook's journey from software engineer to climate modeling expert is both intriguing and illuminating. His extensive research, conducted alongside students at many of the world’s leading climate modeling institutions, leads him to assert that the quality of climate models can hold its own against the intricate software systems developed for mission-critical applications at NASA.

A key caveat Easterbrook emphasizes is the distinction between programming excellence and the accuracy of outputs. In the words of Michael Wehner, a colleague, high-quality code can efficiently produce “the wrong answers faster” if it relies on uncertain assumptions about climate evolution. Thankfully, Easterbrook's book doesn't shy away from addressing these uncertainties. It meticulously outlines how climate models have matured over time and examines the current state of sophisticated models while also acknowledging their intrinsic limitations.

The narrative begins with a deep dive into the historical origins of climate modeling. Easterbrook highlights the pioneering work of nineteenth-century scientists like Svante Arrhenius, who developed the first global climate model even before computers existed. This approach is remarkably insightful, countering the common critique that climate predictions hinge solely on overly complex computer models that few can comprehend.

From here, the book transitions into detailed accounts of Easterbrook’s visits to prestigious institutions such as the UK Meteorological Office, the US National Center for Atmospheric Research, Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace in Paris, and Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Meteorology. Each chapter intricately explores various aspects of climate modeling, although some digressions may feel tangential or awkwardly placed. For example, the chapter entitled “Sound Science” raises questions as it discusses intercomparison projects involving multiple modeling institutions, which may not directly resonate with all readers.

Despite its density, Computing the Climate is not a casual read. It demands focused attention, rewarding readers with a wealth of information. While the main text avoids complex equations, it does provide an array of graphs, charts, and footnotes for those eager for deeper insights. For readers seeking a more introductory exploration of climate modeling, Easterbrook suggests additional literature like The Climate Modeling Primer (4th edition, 2014) by Kendal McGuffie and Ann Henderson-Sellers.

However, given the book's information-rich nature, minor inaccuracies may arise. For instance, Chapter 1 states that key models from a 1979 report “focused on the physical climate system,” particularly emphasizing global wind and ocean current patterns. In reality, these early models did not incorporate ocean currents. Furthermore, claims about the potential doubling of CO2 emissions by the 2030s or 2040s appear to misalign with historical data; pre-industrial CO2 levels were about 280 parts per million, and doubling would yield an implausible 560 ppm based on the accompanying figure.

In the final chapter, Easterbrook takes a broader perspective beyond modeling, asserting the pressing need for urgent action against CO2 emissions. “Consequences [of CO2 emissions] are all around us,” he remarks, a sentiment echoed by many climate scientists. However, establishing direct correlations between specific weather phenomena—such as storms, heat waves, and droughts—and CO2 emissions is a complex undertaking. Easterbrook aptly notes, “Climate models are excellent at giving the big picture, but still leave us in the dark about exactly how each of us will be affected.”

The chapter culminates with a straightforward goal: limiting global average warming since the Industrial Revolution to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit). This figure has faced scrutiny, with some advocating for a more stringent target of 1.5 degrees Celsius, which has already been reached. “The world must not burn more than a trillion tonnes of carbon. Ever,” Easterbrook states, emphasizing the need for a paradigm shift in how society addresses climate change. However, it’s worth noting that such conclusions often intertwine with political beliefs, leading to divergent views on the efficacy of government intervention versus market-driven solutions.

Ultimately, Easterbrook aims to “tell the story of how these models of the physical climate system came to be, what scientists do with them, and how we know they can be trusted.” While he articulates this narrative well, the blanket assertion of “trust” can be problematic. The book transcends mere advocacy; it thoughtfully delineates which aspects of model outputs can be deemed reliable and which cannot. These insights make it a valuable read for individuals on both sides of the climate debate, whether they support a Green New Deal or are skeptical of governmental approaches to climate action.

You might also like: