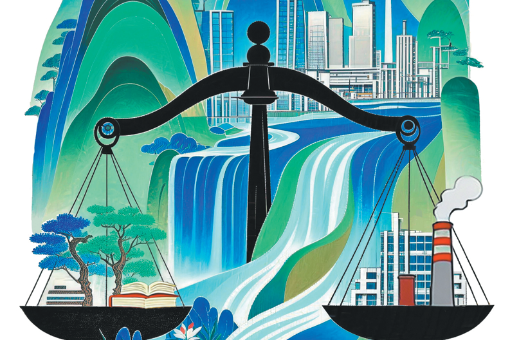

Can We Really Blame Big Oil for Climate Change? Shocking Truths Revealed!

As the world grapples with the escalating impacts of climate change, the conversation often centers around individual actions—recycling, eating less meat, and reducing one’s carbon footprint. Yet, this focus on personal responsibility obscures a more critical issue: the systemic sources of carbon emissions that demand significant reform. While individual actions are important, they are insufficient to address the scale of the climate crisis, which sees the planet's poorest nations suffering disproportionately for a crisis they had little role in creating.

The science of climate change is straightforward: rising levels of carbon dioxide trap heat in the atmosphere, leading to alarming consequences such as severe droughts, rising sea levels, and the extinction of various species. Despite this, public discourse often simplifies the narrative to familiar offenders—cars, coal plants, and livestock emissions—while ignoring the broader systemic issues that contribute to these emissions.

Take, for instance, the energy used globally for heating homes in winter; it equals all emissions from cars combined. Furthermore, the production of a single electric vehicle generates as much carbon dioxide as constructing just two meters of road. Transitioning to electric vehicles is a step forward, but it doesn’t eliminate the emissions generated during road construction. This reality illustrates how emissions are interwoven into the fabric of economic activity, extending beyond individual choices.

Data indicates that 63% of global emissions are linked to poorer or developing nations, which are striving to reach a middle-class lifestyle. Pressuring these countries to cut back on emissions can be seen as an attempt to stifle their development—a stark contrast to the path rich nations took to achieve prosperity without similar restrictions.

The situation is palpably illustrated through the use of concrete, which is responsible for 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. While it remains the fastest and most cost-effective method for building homes and infrastructure, it poses a dilemma for developing nations that prioritize basic shelter over environmental protection. Similarly, the agricultural sector presents its own challenges. As the global population is projected to reach approximately 11 billion by 2100, modern food production methods heavily reliant on fertilizers are set to impact emissions significantly. The use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers emits nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas nearly 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Additionally, methane emissions from livestock contribute substantially to overall agricultural greenhouse gases.

Even though technological solutions exist—such as direct air capture, which can remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere—the associated costs can be astronomical, ranging from $6.3 trillion to $15 trillion annually. Implementing these technologies in heavily polluting industries could potentially double the cost of their products, forcing many companies into bankruptcy.

There is a prevailing narrative that climate change is a collective responsibility, promoting the notion of a "personal carbon footprint." This perspective can be misleading, as it allows for the shifting of blame from major carbon emitters to the average individual. For context, if every person on Earth eliminated 100% of their emissions for the rest of their lives, it would only offset the equivalent of one second of emissions from the global energy sector. Such statistics can lead individuals to feel less guilty or even complacent about their contributions to the crisis.

Politicians must recognize that addressing climate change is not merely a moral imperative but a significant factor in political viability. Efforts must move beyond symbolic gestures like banning plastic straws to target the largest sources of emissions—primarily coal and oil. Comprehensive policy measures, including robust support for green technologies and substantial investments in innovation, are essential. However, if industries resist, strict regulations may be necessary to enforce compliance, potentially even leading to the shutdown of noncompliant firms. With adequate investment, this approach could disrupt existing cycles and lower prices over time.

While there will be trade-offs associated with such policies, it’s crucial to acknowledge that every solution comes with potential downsides. Each individual can contribute positively, not out of guilt for not making a significant impact but in pursuit of the systemic changes necessary for a sustainable future.

The urgency to shift the climate conversation from individual actions to structural accountability is clear. Embracing this broader view is essential if we are to mitigate the severe consequences of climate change and protect our planet for future generations.

You might also like: