Australia's Marine Life Could Face Extinction: Are 'Safe Zones' Vanishing in Just 15 Years?

A new study reveals that Australia’s most protected marine habitats are on a precarious path, facing extreme impacts from climate change by 2040. Even in optimistic climate scenarios, ocean conditions that are considered extreme today will become the norm within just 15 years, threatening a myriad of marine species.

The study, published in the journal Earth’s Future by the American Geophysical Union, indicates that almost none of Australia’s vast ocean territory will provide “safe havens” to shield marine life from the adverse effects of climate change. These “refugia” are essential areas where species might adapt to changing conditions, but they are expected to all but vanish in the coming decades.

Lead author Alice Pidd, who is pursuing her PhD in quantitative ecology at the University of the Sunshine Coast, explains, “When we think about marine protected areas, we might imagine fences or boundaries in the ocean. In reality, these boundaries are ethereal and porous to a changing climate.”

Marine protected areas (MPAs) cover approximately half of Australia’s 7 million square kilometers (2.7 million square miles) of marine territory. These areas are legally designated to conserve biodiversity in crucial habitats like coral reefs, kelp forests, seagrass beds, and mangroves. However, previous research on how these protected zones will adapt to the mounting effects of climate change, including threats to species like whales, sharks, and commercially important fish, has been limited.

Pidd noted, “Marine protected areas are important tools in reducing the impacts of human activities such as fishing, shipping, mining, and tourism. But they weren’t designed with the realities of climate change in mind, and their location alone won’t protect them from its impacts.”

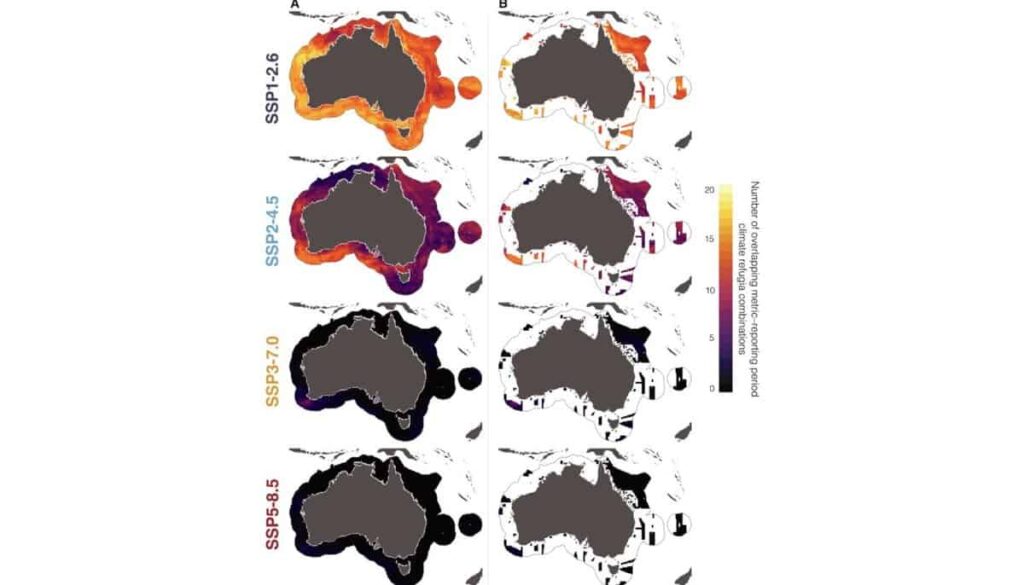

The research team analyzed how Australian waters would respond to various levels of climate change over this century by inputting four different greenhouse gas emissions scenarios into 11 Earth system models, processing several terabytes of data. Their findings reveal that if global temperatures rise more than 1.8 degrees Celsius (3.2 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels, the marine climate refugia in Australia will almost completely disappear by 2040.

Dr. Pidd emphasized that while reducing emissions could allow some refugia to reappear after 2060, “we have already crossed several climate tipping points. Biodiversity will need to adapt.” She further pointed out that conditions under 1.8 degrees of warming would bring about more extreme situations than any recorded from 1995 to 2014, including increased temperature and acidity, lower oxygen levels, and more frequent marine heatwaves. These changes would happen at a pace faster than any recent climate transitions, exacerbating the challenges for marine species to adapt or relocate.

The Vulnerability of Marine Protected Areas

When focusing specifically on Australia’s marine protected areas, the study found little difference in their vulnerability compared to unprotected areas. Co-author David Schoeman, a professor of global change ecology at the University of the Sunshine Coast, stated, “The results are unfortunately not surprising. Marine protected areas will be as vulnerable as unprotected ocean areas when faced with rapid warming, oxygen loss, acidification, and heatwaves.” The highest vulnerabilities were identified in the protected areas off northwestern and eastern Australia.

Traditionally, MPAs have been designed to cover a wide range of species based on their historical habitats. However, Schoeman noted, “the past is no longer a good guide to the future,” as many species are shifting their ranges across static protected area boundaries in response to climate change. Consequently, MPAs may not effectively conserve biodiversity in the future.

The authors argue for more climate-smart marine protected area designs that focus on safeguarding remaining climate refugia, where species may have more time to adapt. They advocate for corridors between these refugia, enabling species to relocate as ocean conditions change. Pidd expressed an interest in future research aimed at identifying where these “stepping stone” corridors might be most beneficial: “The key is to protect where biodiversity is likely to be in the future, not just where it is now.”

Australia's upcoming review of its marine protected area management in 2028 presents a vital opportunity to incorporate these adaptive measures into conservation planning. However, the research team emphasized that enhancing MPAs alone is insufficient; urgent and aggressive actions to reduce carbon emissions must remain paramount to mitigate the projected climate impacts. Pidd concluded, “Doing nothing is not an option. Every fraction of a degree counts.”

You might also like: