China's Shocking Climate Gamble: Are They Really Ready for a 30% Increase in Disasters?

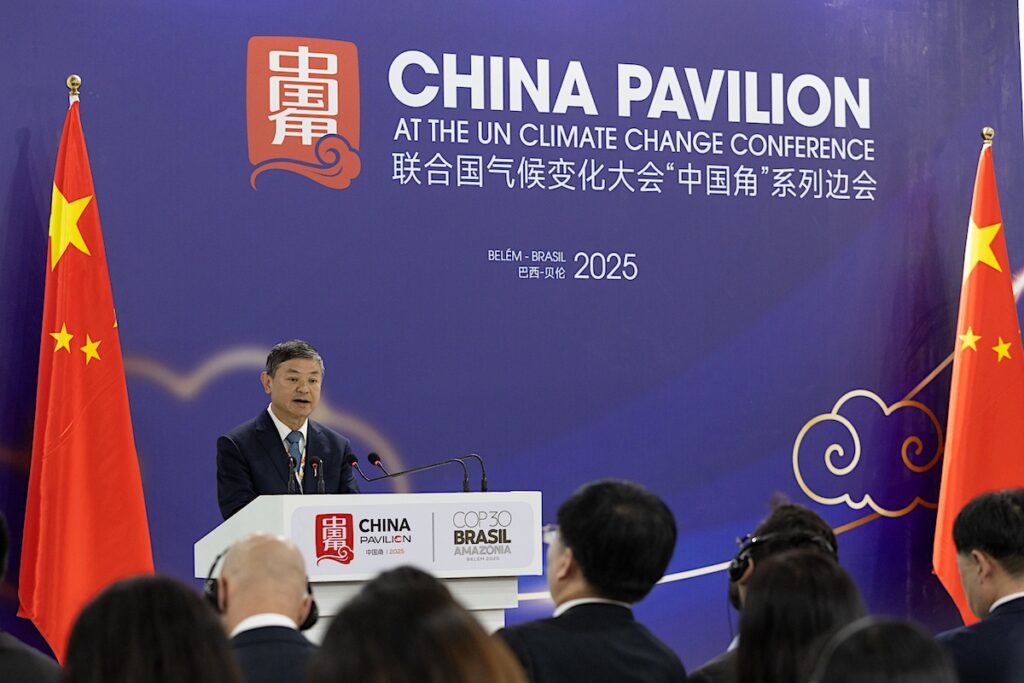

At the recent COP30 climate conference held in Brazil, a striking contrast unfolded. Outside the Amazonian venue, 160 diesel generators rumbled continuously, filling the tropical air with smoke and noise. Inside, massive ventilation units worked to lower the temperature but only added to the cacophony, underscoring the irony of a gathering aimed at combating climate change while relying on fossil fuels.

The conference, attended by leaders from around the globe, focused on a critical topic: how nations can adapt to the long-term impacts of climate change. Key discussions included funding adaptation efforts and establishing a framework to track progress. Would developing countries receive increased financial support to implement on-the-ground solutions? Could a unified approach be developed to assess national advancements that would inform funding decisions?

China’s Adaptation Strategy

Particular attention was paid to China, the largest developing country, as it transitions from a reactive stance toward climate impacts to a more proactive adaptation strategy. A week prior to COP30, China submitted its latest climate action plan, known as a Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement. This plan included, for the first time, commitments to create a "climate-adapted society" by 2035. The strategy reflects a shift to dual efforts in both adaptation and mitigation—essentially, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Rebecca Nadin, director of global risks and resilience at ODI Global, noted that both China’s adaptation plan and the EU’s strategy emphasize data-driven risk assessment and regional adaptation. However, they diverge significantly in governance approaches. The EU employs a decentralized model, empowering local entities and integrating adaptation across various sectors with nature-based solutions. In contrast, China’s approach is centralized, integrating adaptation into national economic plans with a primary focus on hard infrastructure measures like flood control and disaster prevention systems.

“China allocates significant resources, especially for large-scale infrastructure, but EU adaptation finance is more diversified,” said Nadin.

China's adaptation needs are substantial; industries will require over CNY 2 trillion (approximately USD 280 billion) annually between 2026 and 2030—more than 1.2% of the nation’s GDP. According to the Huzhou Green Finance Institute, over half of this funding is earmarked for improving infrastructure, which is essential as climate change intensifies its toll.

However, challenges remain in other sectors like electricity, transportation, and social work, where adaptation support is still lacking. Chen Yingjie, a researcher at the Huzhou Green Finance Institute, highlighted that water management, agriculture, and infrastructure are particularly vulnerable to the physical risks posed by climate fluctuations.

The Financial Divide

The UN Environment Programme’s Adaptation Gap Report 2025 estimates that developing countries will need between USD 310 billion and USD 365 billion by 2035 for adaptation efforts. This is a significant leap from the mere USD 26 billion that was transferred from developed nations for adaptation in 2023. At COP30, it was agreed that developed nations would increase their adaptation support to USD 120 billion by 2035.

For China, however, the financial landscape is shifting; support from developed nations and loans from multilateral development banks are decreasing. Between 2020 and 2022, China only received USD 530 million for climate adaptation, primarily for reconstruction following the 2021 Henan floods. The Chinese government pointed out that the total international climate funding during these years amounted to USD 2.6 billion, just a fraction of the USD 436.7 billion it allocated for climate measures.

Researcher Shao Danqing from Peking University's Macro and Green Finance Lab emphasized that China's adaptation financing predominantly comes from public resources. However, limited government budgets and a lack of incentives for private investors have led to a significant funding gap.

Mobilizing Resources for Adaptation

According to a 2024 government document, China will require an average of CNY 1.6 trillion (about USD 226 billion) each year for climate adaptation through 2060. This necessitates unprecedented mobilization of climate and green finance. China's financial system comprises two main strands: one led by the People’s Bank of China, focusing on green and transition finance, and the other involving city-level climate finance trials managed by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

While the bank aims to create standards and support policies to enhance investments, the ministry is more concerned with practical applications at the city level, promoting local governments to set up investment and financing mechanisms. Yet, as highlighted by Shao Danqing, the current climate-finance systems remain predominantly focused on mitigation rather than adaptation.

To effectively assess adaptation efforts, the recent COP30 also saw the adoption of a global set of indicators. Xi Wenyi, a research associate with the World Resources Institute, remarked that while quantitative targets in China's adaptation strategy are mainly related to ecosystems, there is an urgent need for more comprehensive indicators that evaluate the tangible benefits of adaptation.

Ultimately, adaptation is not merely about preparing for disasters. Improved infrastructure designed for extreme weather can serve additional community purposes, enhancing residents' quality of life and property values. A recent analysis by the World Resources Institute found that each dollar invested in adaptation can yield a return of ten dollars over a decade, highlighting the economic and social benefits of proactive adaptation measures.

As COP30 concluded, the need for a strategic shift toward funding adaptation rather than fossil fuel subsidies became increasingly clear. With global subsidies for fossil fuels amounting to USD 7 trillion in 2022, redirecting these funds toward climate adaptation will be essential in addressing the stark realities of climate change.

You might also like: