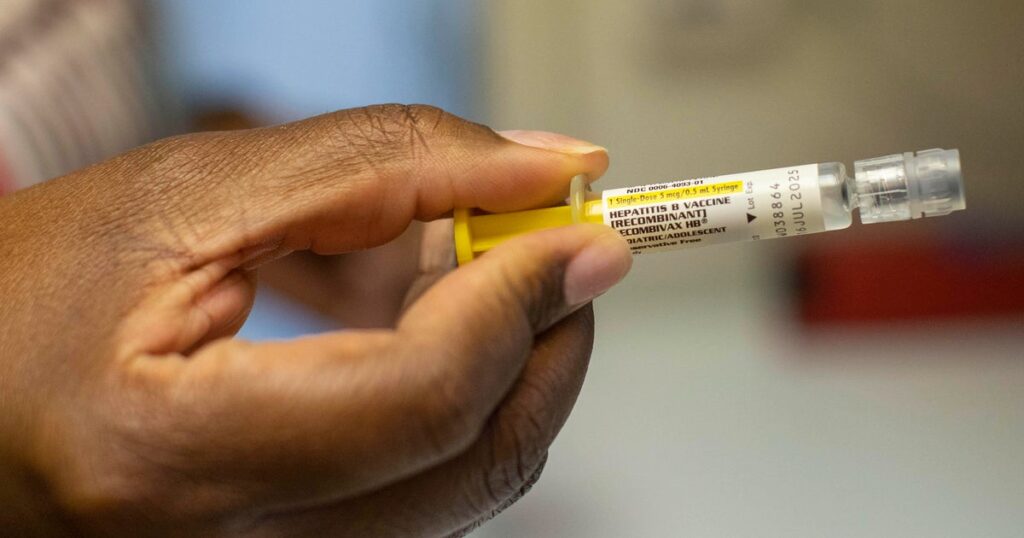

Shocking CDC Vote Looms: Could Your Newborn Face a Life-Threatening Hepatitis B Risk?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is set to convene for two days starting Thursday, focusing on crucial discussions regarding childhood vaccine schedules and recommendations. One of the main agenda items is whether to continue recommending the hepatitis B vaccine for newborns at birth or consider delaying the initial dose.

Since its universal recommendation for newborns in the United States in 1991, research has shown a remarkable 99% drop in hepatitis B infections among infants and children. Hepatitis B is a serious, incurable infection that can lead to liver disease, cancer, and premature death, making the vaccine a critical preventive measure.

Recently, the hepatitis B vaccine has faced scrutiny from vaccine skeptics, including Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who inaccurately claimed in a June podcast that the birth dose may contribute to autism. Kennedy has appointed all current members of the ACIP during his tenure, adding political weight to the discussions surrounding the vaccine's recommendations.

Importance of the Hepatitis B Vaccine for Newborns

The hepatitis B virus spreads primarily through blood and bodily fluids and is known for its high contagion level. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the virus can even survive on surfaces for up to a week, making indirect transmission possible. Infection can occur from mother to child during birth or through caregivers who may be unaware they carry the virus.

The CDC estimates that approximately 2.4 million people in the U.S. live with hepatitis B, with about half being unaware of their infection status. Administering the hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth—referred to as the birth dose—provides up to 90% effectiveness at preventing infection from an infected mother. If infants complete the full three-dose vaccination series, they achieve 98% immunity, according to the AAP.

Newborns infected with hepatitis B at birth face a daunting 90% chance of developing chronic hepatitis B, which can lead to severe complications, including cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. Alarmingly, about 25% of these patients may die prematurely due to the disease.

Historically, prenatal screening for hepatitis B targeted women with higher-risk factors, such as those with multiple partners or intravenous drug use. However, this approach proved insufficient, with a notable percentage of infections going undetected. The CDC maintains that while pregnant women should be tested for hepatitis B, about 16% of expecting mothers do not receive this screening.

The birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine has functioned as a vital safety net, compensating for potential shortcomings in prenatal screening, missed diagnoses, and inconsistent follow-ups. While the vaccine is not mandated for children, many schools and childcare facilities require it for enrollment.

Expert Consensus on Vaccine Safety

Medical organizations, including the AAP and the American Medical Association (AMA), underscore the extensive research supporting the vaccine's safety. It has a long-standing track record, with studies showing no correlation with increased risks of infant death, fever, or autoimmune conditions. Severe reactions are rare, with the most common side effects being mild fussiness.

Dr. Sean O'Leary, chair of the Committee on Infectious Diseases for the AAP, emphasized the vaccine's importance, saying, "It's one of our best tools to protect babies from chronic illness and liver cancer. This is a situation where one missed case is too many." Louisiana Senator Bill Cassidy, who also serves as a physician, expressed concern about potential changes to the recommendations, noting that the birth dose has significantly reduced the incidence of chronic hepatitis B by 20,000 cases over the past two decades.

As the ACIP meeting unfolds, the panel will not only discuss the hepatitis B vaccine but will also deliberate on childhood vaccine schedules, although no vote is planned on this topic. The ACIP previously debated moving the birth dose to one month of age during their September meeting, but they ultimately decided to table the discussion.

Any potential changes to the ACIP's recommendations could have significant repercussions. Recommendations from the ACIP are sent to the CDC director for approval, and while states often base their policies on CDC guidelines, they are not obligated to adhere to them. Changes could also impact insurance coverage for hepatitis B vaccinations, as most private insurers are required to cover vaccines endorsed by the ACIP.

Doctors caution that delaying the first dose or altering the recommendations could lead to an uptick in infections, resulting in both health and economic burdens. Experts have voiced strong opposition to any changes, warning that such shifts could have "lifelong detrimental consequences" and no measurable health benefits. Delaying the first dose increases the risk of infection, especially if an infant receives the virus from a caregiver or during birth.

Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University and a former ACIP voting member, stated, "If you wait a month and the mom happens to be positive, or the baby picks it up from a caregiver, by that time the infection is established in that baby's liver. It's too late to prevent that infection." As the ACIP meeting progresses, the stakes are high for public health, particularly for the youngest and most vulnerable members of the population.

You might also like: